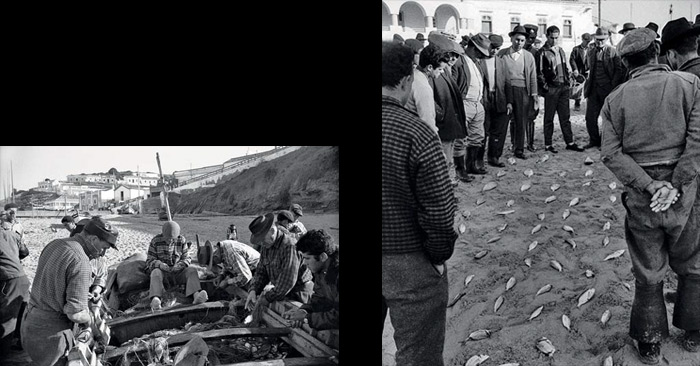

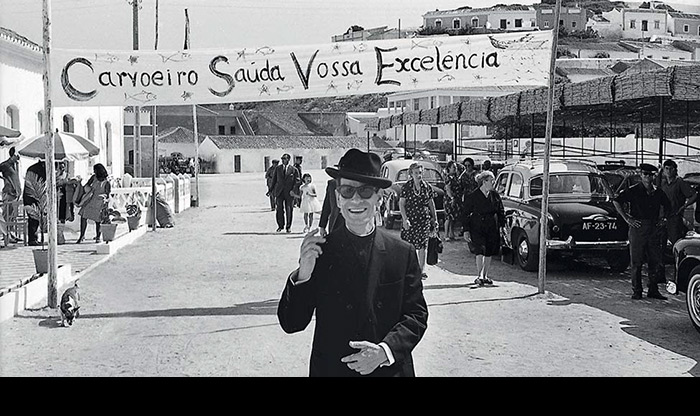

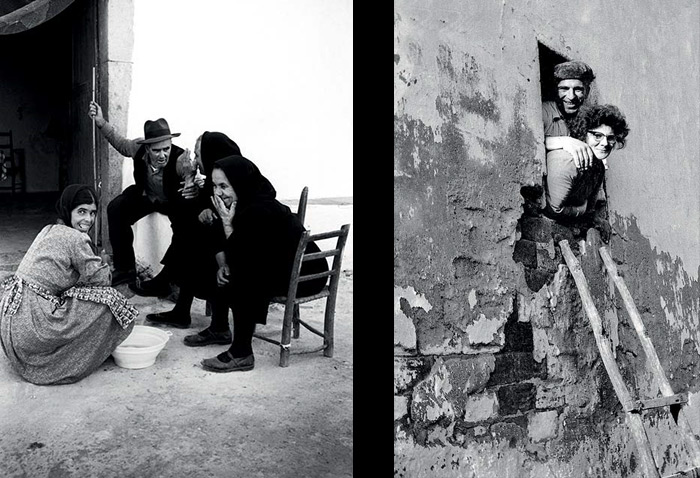

Photographer Tim Motion documented the Algarve during the ´60s and ´70s

London-based photographer Tim Motion documented the Algarve, where he lived, in the ‘60s and ‘70s. A fascinating exhibition of his photographs, entitled ‘ALGARVE 63’, is on display at the Parque Municipal das Fontes de Estômbar (Lagoa), until September 16. In addition to this, a photobook featuring his works will be on sale at the exhibition (€30) and is due to be available online too. Here he reflects on his time in an Algarve that has since changed so dramatically.

I arrived to stay in Carvoeiro on a stormy night in December 1962. The rainwater was rushing like a river down the steep street, past the green house overlooking the beach. This was my new home and I was very happy.

The house consisted of five rooms on the first floor including the kitchen, with bare boards and almost no furniture except two beds with mattresses stuffed with dried maize leaves – a haven for various forms of wildlife. There was a ‘bathroom’ with a cement floor, a non-flushing loo, a washbasin with a tiny mirror hooked to the wall, and a bucket. The bucket, attached to a rope, was for drawing water from the cisterna in the small yard outside, a dampening chore in rainy weather. The village did not have mains water. For hot water there was a large aluminium saucepan on the Calor gas stove. ‘What more do you need,’ I said, besides which the month’s rent was less than that for a week in one grimy room in London with a shared bathroom.

The day after my arrival I looked out of the window to see the entire village square from the beach to the main street under six feet of blown spume from the stormy sea. This was real weather!

There were only six foreigners in the village. The Irish painter Patrick Swift, his wife Oonagh and two daughters Kate and Julie, Claude Bourgier, a French collector of gemstones and budding poet, and his wife Marie, a French-Canadian painter. David Wight, the South African poet, was visiting. He and Swift were later to propose the idea of a book on the Algarve to a publisher in London.

With such a limited pool for social life, any new arrival, even if staying only for a day or two, was invited to dinner, welcomed with quantities of Lagoa wine, Portuguese brandy and Irish whiskey, interrogated, argued with, examined, and entertained with Gaelic songs and recordings of Amália Rodrigues and Alfredo Marceneiro.

The test, which is what it was, a kind of social initiation, was carried out with stringent debate, great wit and good humour. Superficial modishness and pretension were swept aside. For me, a rather naïve lad with a very English upbringing, it was a revelation. Some passed the test, some did not; I am glad to say that with my hard head we drank each other under the table. I was welcomed into the fold.

Fish were auctioned most days on the beach, a short walk from my charcoal grill. Days were spent painting, walking in the landscape, visiting other villages and vineyards. Wine tasting was an integral part of daily life. There was no shortage of bars in Carvoeiro, as the saying was: “Taberna sim, taberna não” meaning every other door was a fisherman’s bar.

The locals welcomed us with curiosity and friendship, and tales of hard times in the past. These were places we frequented often and, with my desire to learn Portuguese, resulted in my acquiring a marked ‘Algarvian’ accent. This caused great amusement on my visits to Lisbon, especially as most Lisbonese dismissed Algarve as being part of North Africa!

There was also the ‘Sociedade’, which was a community hall and bar where Saturday night dances were held. These were formal affairs overseen by mothers and aunts in black at one end, monitoring their daughters in new dresses and the testosterone – filled youths at the other end in their best suits.

The accordionist played tangos and quicksteps, and the swishing sound of shoes across the sawdust-sprinkled floor was a prelude to the mating game. This was not too far removed from the society balls at Grosvenor House in London during

The Debutante Season where eligible young men were listed and assessed.

David Wright returned the next year and work began on the book Algarve – a portrait and a guide. Naturally, as I had a car and a camera, I had a part to play.

The truth is, if I had not been encouraged by Patrick Swift, the selection of photographs for “ALGARVE 63” would not exist as they do. We embarked on this opportunity to observe and record life in Algarve with avid enthusiasm, visiting every church, chapel, taberna, restaurant, fishing port, pottery and local market we could find, communicating with local people.

For me the most exciting and rewarding events, photographically, were the big annual animal fairs at Tavira, Faro and Castro Verde (Alentejo). Oxen, mules, horses, donkeys and cattle were bartered, dominated by the large and picturesque gipsy community. After a long hot day in the dust, we would sit in the semi darkness at a small candle-lit table behind the stalls, demolishing a bottle of medronho, the lethal liquor distilled from arbutus berries.

Life continued in similar vein, with house building and marriage, children and occasional trips back to London and Dublin, until April 1967 when, after a two-year preparation,

I opened a jazz bar or, as the operating licence stated, ‘taberna with music’. There was some difficulty in categorising my establishment as it did not fall within the three basic categories then existent in Portugal – tabernas, Casinos, or what were euphemistically referred to as ‘Dancings’. To describe the whole process of its formation would require another article and the subsequent lifestyle and events, a book.

Suffice it to say that ‘Sobe-e-Desce’ was born and flourished as a disco and jazz club, with barely controlled chaos, fame and excitement for eight years. It was visited by international and local musicians, denizens of the night and high society from Lisbon and Porto, British pop stars, a Duke or two, crazy Brazilians, with after-hours dawn or moonlit swimming on Centianes beach. It was a life far removed from the tranquillity of painting and walking in the landscape.

Text & Photos: Tim Motion